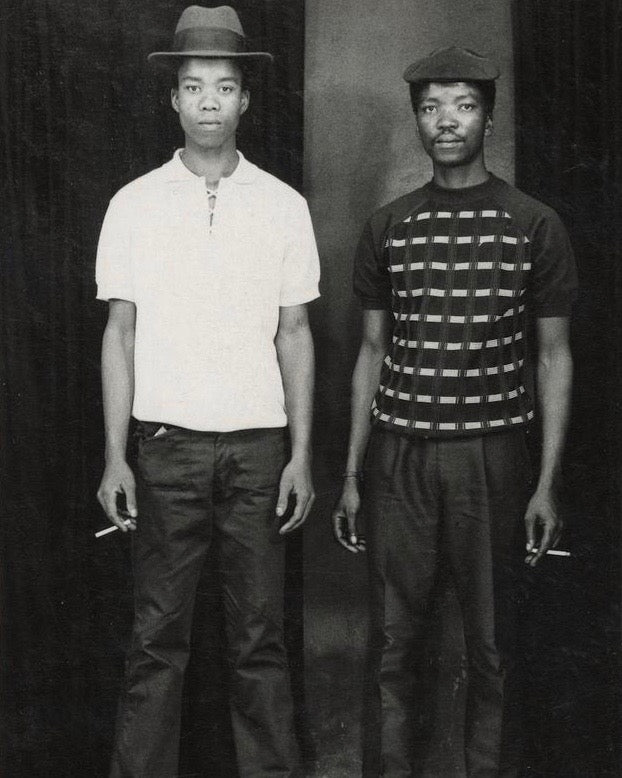

The Archives: 1970's Portraits From South African Photographer Richard Ndimande

South African photographer Richard Ndimande took over his father’s eponymous Z.J.S. Ndimande and Son portrait studio at the height of apartheid in 1968, 30 years after it first opened. Under a challenging set of circumstances but with a family legacy to maintain, Ndimande set out to transform his studio into a safe haven for his subjects, thus creating a joyful space of escape and self-expression.

Growing up, Ndimande worked closely with his father to become well-versed in the intricacies of running a photography studio, especially as he geared up to take over the shop himself. At the inception of the business, the studio used a simple but somewhat bulky box camera, which was popularized at the end of the 19th century. Ndimande eventually transitioned into using a Rollei dual lens camera to create his photographs, which were developed using silver gelatin on resin-coated paper.

The first year he took it over, Ndimande had been forced to move the studio from its near 30-year-old Greytown location (now the KwaZulu-Natal province) due to the new Group Areas Act laws that forbade people of color from living and working in the town. In its new location, the isolated village of Enhlalagahe, crime was pervasive and permits were required to even enter the town, causing Ndimande’s business to greatly suffer. He eventually returned back to Greytown in the 1980s and opened his studio under the deceptive name of Frederick Bob Harris.

As another form of segregation during apartheid, Black people had to carry so-called “passbooks” with them at all times, which contained their picture and any other identifying information. The passbooks were used to enforce racial divisions and limit the movement of the Black population. Historically, the medium of photography has proved to be a potent, and paradoxical, force in the wielding of power: the magic of its truth-seeking quality could equally be used to target the most vulnerable populations.

For Ndimande, his work presents a different, far more empowering narrative of photography. Ndimande’s gift was in allowing his subjects to be portrayed as they wished and saw themselves through his black and white medium. As they sat before a simple opaque curtain with few props, the photographer painted portraits of a complex group of people whose inner workings often went unacknowledged. People of all ages sat before his camera and reveal the playful, pensive, or perhaps even seductive sides to their personalities as they let loose in Ndimande’s studio.

In the images mainly taken in the 1970s, models display their unique sense of fashion, along with providing insight into the trending styles of the era. The popularity of the recently released Converse sneaker is evident, along with the newsboy cap and the A-line dress, a staple of the 1960s. Several Zulu women often appear in traditional clothing and showed off designs of carefully crafted beadwork, a cherished handicraft passed down among the generations. They would top off their outfits with a pair of sneakers or sunglasses.

Other models hold what appears to be personal moments, such as one woman who proudly showed off her record; music was a part of a movement towards extreme censorship dictated by the South African government. In another act of defiance, a different woman poses unapologetically in her underwear with a hand on the hip, safely revealing her true self in a society that largely rejected her for her skin color. Yet, like many other models, the woman still covers up with a large pair of white sunglasses whose dark shades completely obscure her face from the camera.

Similarly, many of the models choose to be photographed with their backs to the camera, such as one woman who wears a traditional Zulu garment. Though self-expression was both allowed and encouraged in the photo studio, it is clear that this came with limitations. The threat of a compromised identity remained an obvious concern, and the realities of the world outside of the studio were unwavering.

In giving his subjects the dignity and power to just be, Ndimande celebrates the joy and individuality of Black South Africans during this period. His beautifully simple portraits offer glimmers of hope and resilience even in the face of adversity. Ndimande passed away in the early 2000s, but his expansive archive of work from the Z.J.S. Ndimande and Son portrait studio has recently been revisited through a March auction at London-based Bonhams, where over 1,000 photographs and four albums sold for £40,062.

The Folklore shares a few of our favorite images from the diverse portrait archive of South African photographer Richard Ndimande.

Words by Olivia Starr