Observations: Sudanese-American Poet Safia Elhillo on Representation

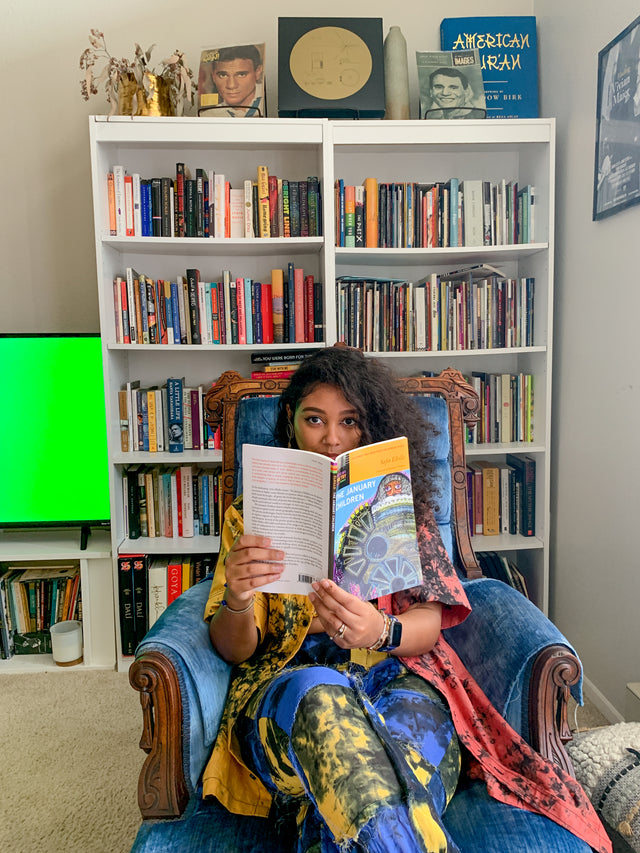

Safia Elhillo, a Sudanese-American poet and Stanford University fellow, uses her writing to look back at her heritage. Elhillo’s experience in the diaspora led her to use poetry to examine identity, migration, nationality, exile, and belonging. Elhillo’s 2017 collection The January Children explored the lasting effects of the British occupation of Sudan along with the tension within Sudanese culture between the country’s Arab and African identities.

In 2019, Elhillo co-edited Halal if You Hear Me, a poetry anthology centered on women with Muslim, queer, trans, or nonbinary identities. She also has a novel, Home is Not a Country, and a collection of poetry, Girls That Never Die, both set to be published in 2021.

The novel, written in verse, tells the story of a child of immigrants struggling with coming of age in American suburbia. Her poetry collection imagines a world of female positivity where misogyny no longer exists. The Folklore interviewed Elhillo about her roots, poetry, and future ambitions, ahead.

There's a duality between English and Arabic in your works, can you explain the significance behind that decision?

"In those poems, I was trying to get as close as I could to how language functions in my brain. If I’m speaking entirely in English or entirely in Arabic, then there’s always a part of me that’s translating. I feel most comfortable talking in this sort of hybrid language, where the words can be in Arabic or in English and I don’t have to make sure what comes out of my mouth is entirely in a single language.

I also don’t feel fully fluent in either language, so I feel like I have more language at my disposal if I harness these two partial fluencies, because to spend time in one or the other would be to realize how much fluency I lack. I was trying to exercise some of the shame that comes from this lack of fluency by accepting that there’s a third language that forms in the hybrid space between the two, between Arabic and English, and that language is my language, the language I am fluent in.

In situations where I’m most comfortable, that’s the language I speak. My mother and I, or my brother and I, or my cousins and childhood best friends, we speak in this combination of Arabic and English — the word comes out in whatever language I was thought in. I was trying to write poems that look like what it sounds like in my head."

What's your relationship with Sudan, how often do you visit Sudan and how much of your heritage plays into your inspiration?

"Until recently, I used to go back to Sudan every year. It was easier when I was in school and had guaranteed time off. Now it’s been a few years. My last trip to Sudan was in 2016 and I kept extending my stay because I didn’t want to leave.

I was in Sudan when I got the call that The January Children had won a prize and was going to be made into a book. I wrote a lot of those poems while I was in school doing my MFA in New York, but I took notes for what became a big chunk of the final book during that month I spent in Sudan. To be back at the conception site of the book and hear that it was going to become a book was unreal.

It’s definitely a big inspiration for my writing. I always think that maybe in another life I would have wanted to be a historian and being a writer in this one is a way of gesturing towards that. So much of my writing comes from a place of wanting to know what happened, how we got here.

My family tells all these beautiful stories very casually. No one was writing them down because it just was so casual. So, I wanted to write them down and make a record, a container for them and to get these stories to outlive my body, to outlive the people who told me these stories. I’m simply trying to make a record of the things that I’ve been told about, from where I come from, what came before, and how I got here."

As a child of the diaspora, did your family continuously pressure you to know your origins? Did anyone from within your culture judge you on your journey of becoming a writer?

"Being a poet is nothing new in my family. My maternal grandfather is a poet, and so were several of his sisters, and my maternal aunt is a poet and playwright and filmmaker. Therefore, it wasn’t a huge surprise when I became interested in poetry and writing. I’ve been a big reader my whole life, and my family has always known that about me.

Plus, poetry is celebrated and beloved in Sudanese culture, so I’ve never felt judged for the choice. For the most part, I’ve felt very held and celebrated by my community, and I’m grateful for that.

I grew up feeling very Sudanese, very in touch with my Sudanese identity, not because of pressure, but because it felt like the only real constant in my early life. Before moving to the US when I was 10, my family lived other countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, England, Egypt, Switzerland. My world outside was constantly changing, but the world inside the house always felt the same, smelled the same, played the same songs, ate the same food, spoke the same language, and I found a lot of safety and security in that."

Like other creative industries, poetry is no different from the circle of being driven by old, white males, how do you find the motivation to bring change to the industry?

"For so long, I wasn’t seeing my particular intersections of experience represented in the literature I was reading, and this sometimes made me feel like I didn’t exist. The more we write our stories down and get someone to read them, the more we have a record that we existed.

That we are not a monolith and the more we can continue to dispel the obsolete and boring idea that only old white men have experiences deserving of literature. I want to see my people taking up space and making books, films, songs, TV shows, photos, and fashion — all of it.

And I want to see representation beyond just being seen, I want my people to be heard and I want the full range of our experiences to be given space, instead of just one of us being treated as representative of a whole community. I never want to be in a conversation where I am being regarded as a 'first' or 'only' because I’m not the first anything or the only anything.

I am motivated to do my part in populating poetry, literature, and the creative world to reflect the world I actually live in — which are not driven by old white men and have those communities speak for themselves in their gazillion perfect voices."

Words by Eman Alami